Tough Questions to Ask about Trinity edX

This essay expands on themes raised in my earlier presentation, “Lessons Learned from Teaching MOOCs at Liberal Arts Colleges: Reflections on Data Visualization for All,” delivered at the Blended Learning in the Liberal Arts Conference at Bryn Mawr College, PA, in May 2017. See my presentation slides.

Dan Lloyd, my faculty colleague in the Philosophy Department, asked several of us to report on our experiences with Trinity edX (sometimes called TrinityX), the non-credit open-access online course platform that Trinity College joined as a partner in 2014. To date, Trinity faculty have developed at least seven edX courses, with more underway, on topics such as art and chemistry, mobile computing, data visualization, biology education, urban sustainability, and the philosophy of phenomenology (see https://www.edx.org/school/trinityx). Three years later, it’s time for Trinity to re-evaluate our edX partnership. This essay raises tough questions that we should be asking ourselves about multiple goals of this initiative, its direct and hidden costs, and how we should make decisions in higher education.

Since edX is an “open access” initiative, I am sharing my reflections in this public essay, rather than a private email that only Dan and a few others might read. To those who already know me, it’s no surprise that my views on educational technology are “mixed.” On one hand, I value meaningful student engagement and believe in seeking out innovative ways to deepen and expand learning for all. The edX initiative asks us to rethink our classroom teaching with technology, a process I began first-hand in the late 1980s and continue today. On the other hand, my graduate training in educational policy studies has inoculated me with a healthy dose of skepticism toward technology innovations. The best way to avoid the twin contagions of hype and greed is to expose ourselves to thoughtful analysis of these trends by historians (such as Larry Cuban, Teachers and Machines) and contemporary critics (such as Hack Education by Audrey Watters).1 Of course, my experiences and views of edX may not be representative of other faculty, staff, and students at Trinity. To quote my colleague Dan, “your mileage may vary.”

How we got here

One obstacle to clear thinking about Trinity edX is how it emerged in an era of hyped-up expectations for transforming higher education. The New York Times declared 2012 to be the “Year of the MOOC.”2 Stanford professor Sebastian Thrun, who created the for-profit Udacity platform for free online courses, predicted that in 50 years, “there will be only 10 institutions in the world delivering higher education.”3 At Trinity, my colleagues on the Information Technology in Education Committee (ITEC) organized discussions to make sense of this movement, with faculty who gained first-hand experience as students in MOOC courses, and thoughtful guest speakers such as Lisa Spiro (who provided an overview of how liberal arts colleges were responding) and Lisa Dierker (a Wesleyan professor who innovated with teaching on the Coursera platform). Although research universities led the MOOC movement, several liberal arts colleges climbed aboard the bandwagon that promoted massive open online courses as a grand experiment to reshape higher education. Soon thereafter, some of Trinity’s peer institutions — Wellesley, Colgate, Davidson, and Hamilton — joined up with the non-profit edX platform (created by MIT and Harvard), while faculty at Amherst voted to stay away.4

Trinity’s leadership decided to join up with edX. In December 2014, Dean of Faculty Tom Mitzell announced that Trinity would sign a 3-year contract, with an initial start-up fee of $250,000 (see more details about costs below), which committed our faculty to develop at least 4 non-credit open online courses for the edX platform each year. The Dean’s letter emphasized how our institution would benefit by experimentation and reputation, while the larger world would benefit from the free expansion of knowledge.

Joining edX will enable the College to expand its educational outreach to people in the broader community, including individuals in Hartford, our alumni, high school students, and others in the U.S. and abroad. . . This partnership with edX represents an opportunity to publically promote the quality of instruction embodied within a Trinity education, enhance our reputation, and influence the evolution of online instruction. It is an opportunity to conduct experiments, research how students learn with online content delivery, and provide open access to liberal arts teachings. We will be joining an elite set of liberal arts institutions that have already begun to explore the myriad possibilities associated with an edX partnership. (Dean Tom Mitzell to Trinity Faculty, December 16, 2014).

The letter also mentioned the possibility that edX might generate some revenue for Trinity if students paid for verified certificates of completion of these free online courses, but let’s leave that point aside.

Admittedly, I sat on the sidelines during this phase, and did not actively support nor object to the Trinity edX contract. By 2014-15, my term on the ITEC committee had ended, and I was on research leave from Trinity with a fellowship at another institution. But my worries grew when I participated in a not-well-attended information session for faculty members who were considering teaching a edX course. Exactly how would Trinity determine whether or not this high-cost program achieved its vaguely-defined goals? Some of my faculty colleagues expressed similar concerns in the Trinity edX Committee’s 2015-16 report. The report listed the first cohort of courses, described several implementation challenges, and also brought up the key unresolved issue:

The Committee began preliminary discussions on how to assess the ‘success’ of online courses. At this early stage it was not clear what the evaluation criteria might be. (Trinity edX Committee Report, 2015-16.)

Reflections on my edX teaching experience

To understand more about the Trinity edX process first-hand, I submitted a proposal to design and teach a course during its second year. Although my colleague Dan Lloyd impressed me by designing a 6-week online non-credit philosophy course that also became a module for his face-to-face for-credit Trinity course, I could not fathom how to accomplish this with courses that I regularly taught, which relied on writing assessments that did not easily convert into online activities (or God forbid, more papers to grade!). Faculty at other liberal arts colleges who had experimented with MOOCs warned against doing any assessment that involved writing. Furthermore, I already shared the syllabi for my existing courses — with many examples of student writing — on the public web, so I did not see benefits of moving this content into the open-yet-password-protected edX platform.

See all Trinity edX courses at https://www.edx.org/school/trinityx

See all Trinity edX courses at https://www.edx.org/school/trinityx

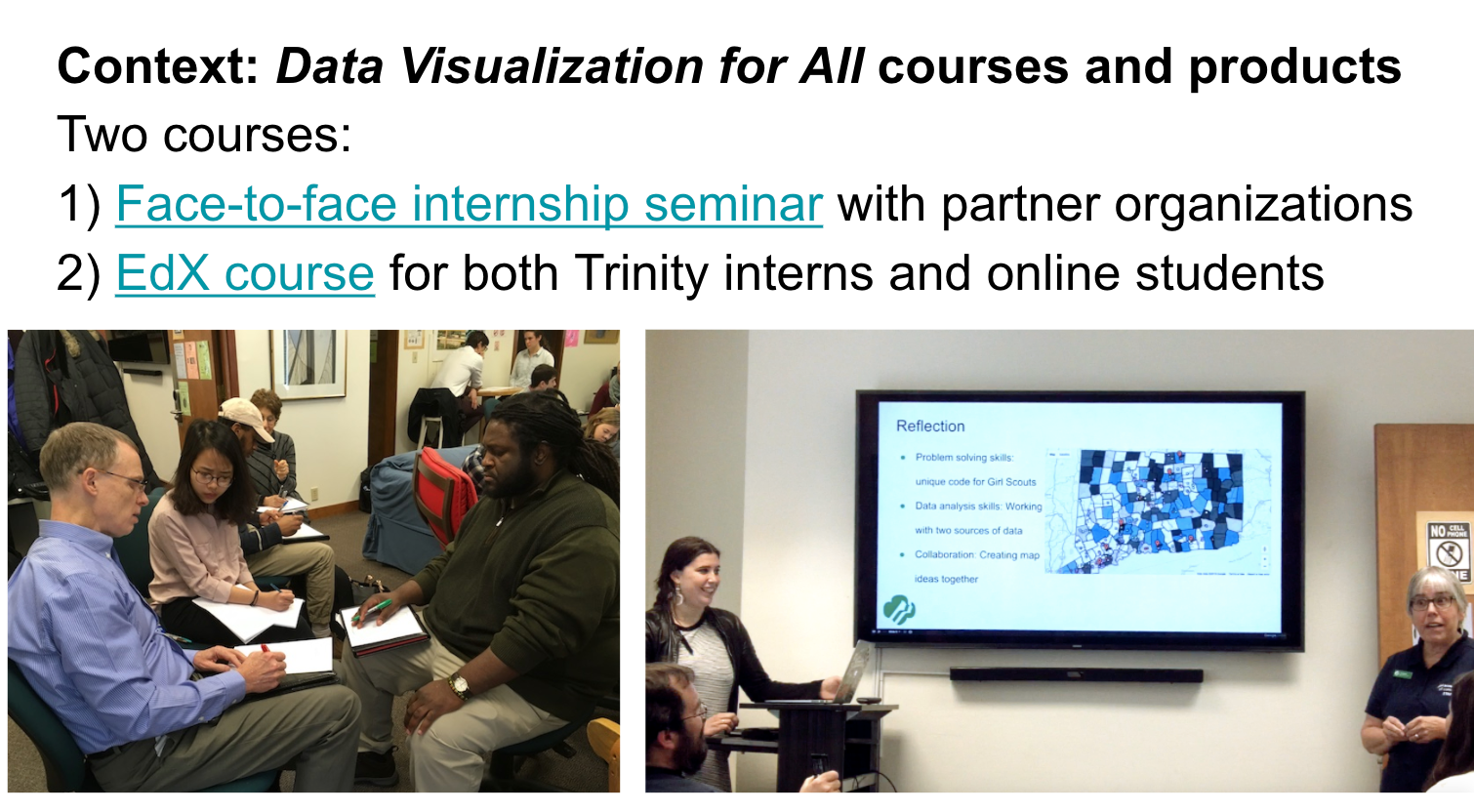

After considering my options (and time constraints), I proposed to create a non-credit online Trinity edX course titled “Data Visualization for All” for Spring 2017. The description included the all-important tagline: learn how to tell your data story with free and easy-to-learn tools, and create interactive charts and maps on the web. I chose this course topic, rather than one of my writing-intensive courses in educational history or policy, because I had already shared several data visualization instructional materials on the web, which many readers had discovered. Furthermore, I could envision how to expand my existing web content into a online course with automated or peer-reviewed assessments, for multitudes of students who I would never meet, nor have time to interact with in person. Building loosely on Dan Lloyd’s model, I designed my edX course to run parallel to a small one-hour-per-week data visualization internship seminar I also supervised that semester, though it did not count as one of my regular courses. As a result, two groups of students used these instructional materials: the 9 Trinity students enrolled in my face-to-face weekly seminar, and many more students who enrolled in the online course (see more about edX enrollment data further below).

One way that my experience diverges from the typical online instructor’s story is that “Data Visualization for All” actually consists of two open-access products: the edX course and a free online textbook. We used the edX platform to publicize the course and register students, and to lay out a 6-week course outline, with short conceptual videos, multiple-choice quizzes, peer review assignments, and a discussion board for anyone needing help. But most of the course content — such as step-by-step tutorials, sample data sets, and templates — appeared in a separate, open-access digital textbook. Students in the edX “course” followed links to the “book” on a different platform. The open-access book is a separate product for several reasons. First, the edX platform was suboptimal, from my perspective, and I did not wish to pour hours of work into a customized HTML-only format that was not designed for easy export to other platforms. By contrast, I authored the textbook on a GitBook platform, which uses the easy-to-write Markdown format, and content is shared and exportable on a GitHub repository, an open-data standard. Second, while all content in my edX course is open access, it sits behind a password-protected site, and is not easily discoverable through search engines. Third, as much as we praise teaching, the faculty promotion systems are driven largely by publications. Although it’s “just a textbook,” my online textbook is far more likely to be recognized by my peers as a publication, in contrast to a MOOC.

Learn how my edX non-credit online course ran alongside my for-credit face-to-face Trinity internship seminar http://commons.trincoll.edu/dataviz, and how my co-authors and I produced an open-access textbook, Data Visualization for All (http://DataVizForAll.org)

Learn how my edX non-credit online course ran alongside my for-credit face-to-face Trinity internship seminar http://commons.trincoll.edu/dataviz, and how my co-authors and I produced an open-access textbook, Data Visualization for All (http://DataVizForAll.org)

If you’ve never taught a Trinity edX course, it’s definitely a team effort. I invited two key people to serve as co-instructors to credit their intellectual work in creating the course: Dave Tatem (Trinity’s Instructional Technologist for the social sciences, who helps me think about teaching and learning with data, and managed the edX platform) and Stacy Lam (an undergraduate who had completed my face-to-face internship seminar the previous year, and provided key design insights from a former student’s perspective). Behind the scenes, Angie Wolf (director of operations and planning for Trinity’s computing center) managed all of the videography and editing for about eight 3-minute concept videos. In addition, Trinity student Ilya Ilyankou (a double-major in computer science and studio arts) developed several open-source code templates for the course. He and other students also co-authored chapters for the online book.

As an individual faculty member at Trinity, was I personally satisfied with my edX experience? On one hand, I was tremendously pleased with my campus edX team that worked with me to create the course, and the modest course development funding that Trinity provided to create new digital learning materials for both my face-to-face and virtual students. On the other hand, the edX platform is not as friendly as expected for authors or students. Furthermore, edX staff never addressed my friendly suggestions for minor improvements to their open-source code, which I submitted directly on their development platform. I also asked my campus IT lead to raise one simple coding request directly with our edX campus rep. Finally, I described my minor code request (with a link) in the standard post-course edX faculty satisfaction survey. No one has ever responded.

But “individual faculty satisfaction” is a narrow way for Trinity to address the broader question about whether to continue our edX partnership. In any evaluation, what matters is how we frame the questions, and the ways we gather information to answer them. Ideally, the overarching question for any educational evaluation should be:

Question 1: To what extent does a program contribute to — or distract from — achieving our core mission?

But this seems to be “too big” a question for us to wrap our heads around, as seen in the Trinity edX Committee report from 2015-16 above, where no one had a clear idea about how to evaluate the “success” of our online courses. So let’s break this down into smaller, more manageable questions, perhaps with a more pragmatic focus:

Question 2: What evidence exists, if any, that the program is achieving its stated goals?

Recall that the December 2014 announcement of Trinity’s edX contract stated at least three goals (which I’ve reordered here): experimentation, reputation, and expansion of knowledge.

a) Experimentation and research with online student learning:

One of Trinity’s stated goals was to “conduct experiments [and] research how students learn with online content delivery.” Yet to my knowledge, no one at Trinity has collected or analyzed any meaningful evidence about student learning through our edX courses, or shared this with me (as one participant) or our faculty at large. Nor am I aware of any systematic sharing of quantitative or qualitative learning data across comparable liberal arts colleges on the edX platform. At the 2017 Blended Learning in the Liberal Arts Conference at Bryn Mawr College, my Trinity colleague Dan Lloyd and I told stories about edX experiences, along with an IT colleague from Wellesley, which was a great first step, but not the same as systematic research.

If no one collects data, nor systematically analyzes it, does this really deserve to be called an “experiment”? Sorry if that sounds a bit harsh. But if a philanthropic foundation granted me funding of this size to run an new educational program, you can bet that they’d insist on an evaluation component from the start. In the not-for-profit world of academia, collecting, analyzing, and sharing meaningful data about teaching and learning — the core mission of liberal arts colleges — should be a central part of our mission, not an afterthought.

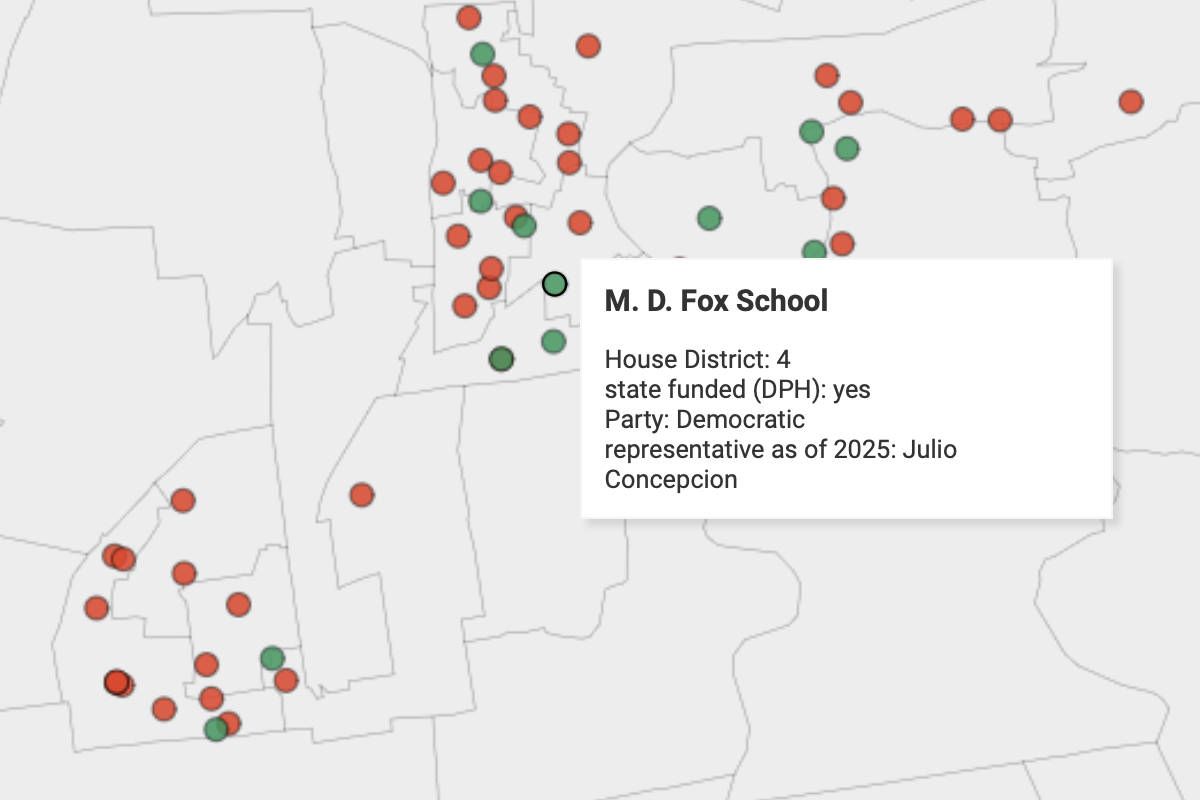

In the absence of meaningful analysis, institutions like mine tend to fall back on not-so-meaningful public relations statements about our experiences with edX. For example, consider this basic question: Who enrolls in Trinity edX courses? At an April 2017 faculty meeting, our top administrator made this statement, which is accurate: “Through these non-credit bearing courses, involved faculty have engaged with over 25,000 students from over one hundred countries.” In fact, as part of my Data Visualization for All course, I encouraged registered students to answer a simple survey question in an open data format, which allowed anyone to map the general location of participants, as shown below.

Data Viz for All, Spring 2017 survey participant map, https://handsondataviz.github.io/lmwgs-dataviz-2017-spring/

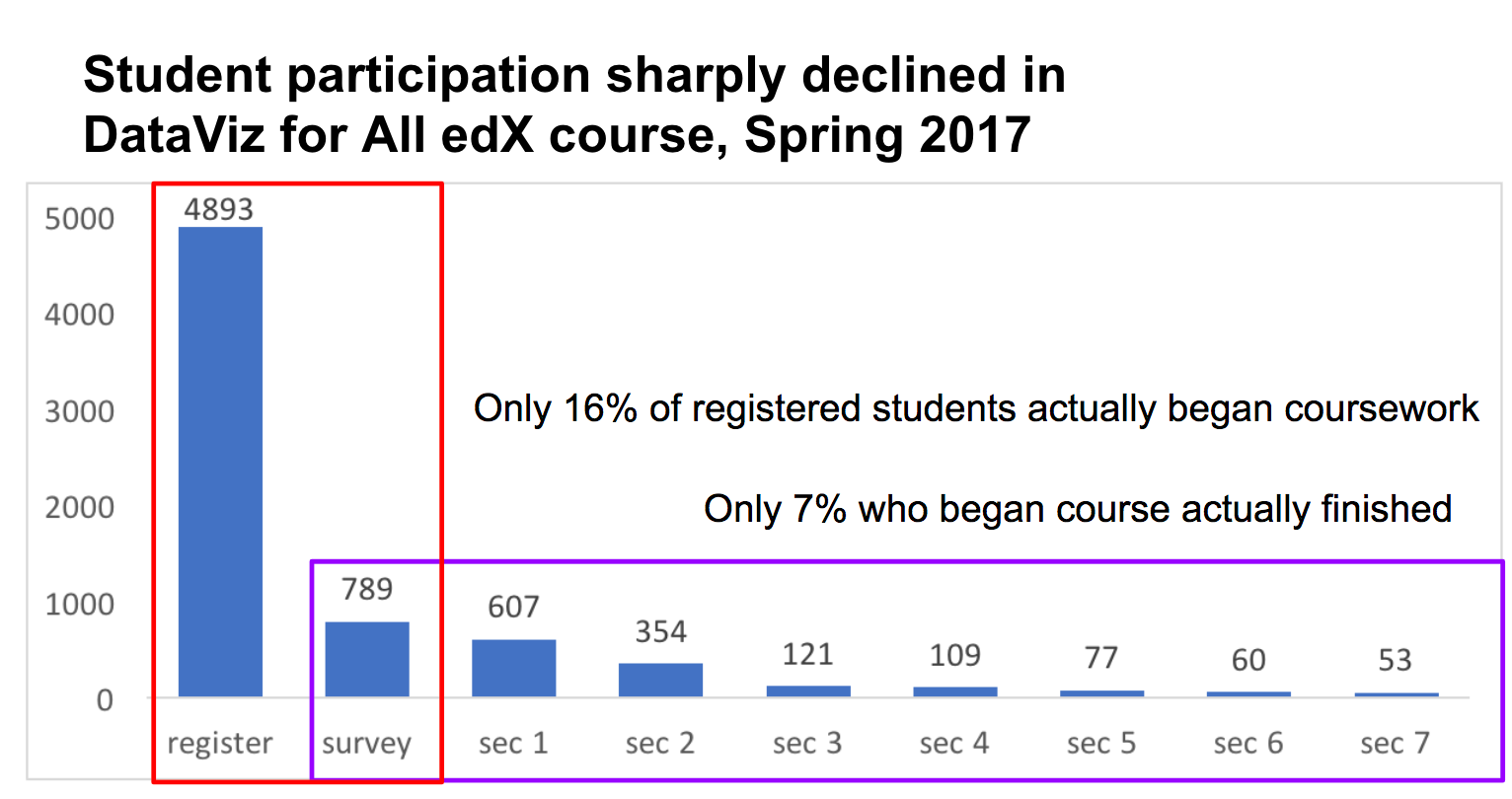

Yet while this public-relations statement about Trinity edX is accurate, it does not reveal the full picture of what learning actually looks like. In my “Data Visualization for All” edX course in Spring 2017, online student participation sharply declined during the two-month run, as shown by course statistics. Although nearly 5,000 students registered for the free course, less than 800 (16 percent) of those actually began the coursework by filling out my initial survey described above. Moreover, only 53 students (or 7 percent of the roughly 800 who began the coursework) finished it by the end.

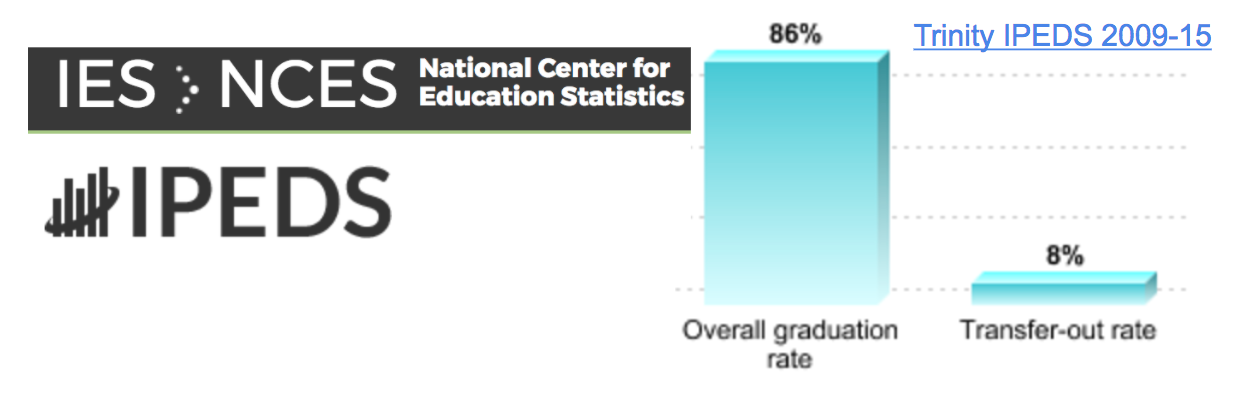

Is the completion rate (or “dropout” rate, if you prefer that term) of my course similar to other edX courses at Trinity or elsewhere? We don’t know the answer. To my knowledge, very few institutions publicly release this type of information. That seems counter to the spirit of the open expansion of knowledge goal. Instead, Trinity and other institutions should openly publish MOOC retention data, just as higher education accreditors and government agencies mandate that we report retention data about traditional face-to-face enrollments.

b) Reputation

To date, I have not seen any evidence, quantitative or qualitative, which suggests that Trinity’s reputation has risen as a direct result of partnering with edX or offering our courses on their platform. And I think it’s a difficult argument to support. Imagine that everyone accepted the validity of the reputational survey of liberal arts colleges compiled by US News and World Report (note that this sentence began with “Imagine…”). To convince us that MOOCs had reputational power, one would need to demonstrate that over time, participating institutions (such as Trinity) went up in reputation levels, while non-participating institutions (such as Amherst) went down, holding other factors constant.

Furthermore, it’s not yet clear to me whether students who register for a Trinity edX course clearly identify it with our college in particular. Here’s a researchable question: if an independent organization sent an online survey to students who registered for one of our online courses, and asked them to name our college from a list of similar institutions (such as Connecticut College, Wesleyan University, Tufts University), what proportion of the respondents would accurately identify that it was offered by Trinity? While edX students probably are more likely to recall that a course was offered by well-known institutions, such as Harvard or MIT, to my knowledge, no one has systematically explored this question for smaller liberal arts colleges that are edX partners.

Finally, it’s important to remember that online education is a two-way street. While we hope that our institutional reputation would go up, negative user experiences with the content, platform, or even other users can drive that indicator downward. Digital content ages quickly. Online course material that looked shiny and new in 2014 may not meet the same standards in 2017, and probably will appear to be obsolete to many web visitors by 2020.

c) Expansion of knowledge

Let’s be clear: I’m all in favor of the open expansion of knowledge. It’s the central reason why I’m became an educator, and a core principle in designing “Data Visualization for All.” But MOOCs, like most institutions, do not distribute educational resources equally across the population. The Trinity edX Committee report of 2015-16 briefly noted that “the majority of learners were slightly older than college-age, and had at least some college education,” a common pattern among MOOCs in general. If Trinity is serious about using edX to expand knowledge, we need richer data on the demographics of people currently served, and research-based ideas on more effective ways to reach underserved populations.

Question 3: What are the direct — and indirect — costs of operating the program?

Evaluating any educational program requires a clear accounting of direct costs (which appear in a budget) as well as indirect costs (which may be hidden from view). Since no one has granted me access to actual cost data, here’s my estimate from Trinity’s announcement of its edX partnership in December 2014:

Estimated Direct Costs for Trinity edX

$250,000 one-time edX membership fee

$ 45,000 annual subscription cost (year 1)

$ 45,000 annual subscription cost (year 2)

$ 45,000 annual subscription cost (year 3)

$ 40,000 annual faculty and direct expenses (year 1)

$ 40,000 annual faculty labor and direct expenses (year 2)

$ 40,000 annual faculty labor and direct expenses (year 3)

$505,000 3-year total

Note that annual faculty labor and direct expenses are based on $5k for course development, $3k for running the course, and $2k for expenses = $10k x 4 courses per year.

Now consider some of the indirect costs, which I can only estimate, because no one has shared actual data. The Trinity edX Committee Report of 2015-16 stated that “faculty and staff involved in creating new edX courses made it clear that this process required a substantial investment of time.” First, although faculty like me received an additional stipend of $8,000 to develop and run a Trinity edX course, the actual time commitment cut into our other teaching, research, and service responsibilities. Second, my experience revealed that IT staff had to spend a considerable amount of their time to co-produce and manage our edX courses. Trinity employs 3 instructional technologists and one director to manage them. (Did anyone tabulate the total number of hours spent by instructional technologists per edX course? Might it have exceeded 33 percent of their annual workload, or more? If yes, then add 1 FTE instructional technologist salary and benefits to the direct cost estimate above.) Given that only 4 or so faculty developed an edX course each year, this project swallowed up a disproportionate amount of their workload, and there may be hidden detrimental costs to the other 180+ Trinity faculty who did not develop edX courses, but would have benefitted from IT services.

Update on Nov 29th: Also, note that of the 6 Trinity faculty who developed edX courses that appear online to date, 3 are now retired (Archer, dePhillips, Morelli) and the other 3 of us are full professors (Lloyd, Myers, and me). This suggests that Trinity edX does not match the needs of the majority of our younger faculty.

Once again, the figures above are simply my quick estimates. If Trinity College wishes to continue the edX partnership, it should give serious consideration to tabulating real costs and sharing those with a faculty committee. Until that happens, my ballpark estimate suggests the price tag of this 3-year experiment was at least $600,000, and probably higher.

Question 4: Do the benefits justify the costs? Have we explored alternative ways to achieve the same goals?

No one wants to reduce educational policymaking to a mechanistic cost-benefit analysis, because so many of our values — such as understanding, collaboration, and freedom — cannot be measured in dollars and cents. But ignoring the true costs of educational programs, or failing to connect programs to their intended benefits, are equally unwise choices for the long-term health of institutions such as Trinity. At this three-year threshold in the Trinity edX partnership, we need an sober evaluation on whether our investment of significant time and money produced the outcomes as envisioned. Speaking as one faculty member, I am not persuaded that the edX experiment, if we can even call it that, should continue.

Perhaps it’s easier to think about this challenging question in a different way. Has Trinity explored alternative means to achieve the same goals: experimentation, reputation, and expansion of knowledge? Instead of spending more than a half-million dollars on online education, how else could we spend a fraction of that money to achieve similar ends? Some quick ideas:

a) If Trinity values experimentation to improve teaching and learning, should we consider funding better ways to collect evidence of this in face-to-face settings (such as rich observations of classroom and non-classroom interactions), to help us better understand when and how we are reaching our goals, and expanding these lessons across the college?

b) If Trinity values improving the reputation of our core mission, face-to-face teaching and learning, should we fund better ways to capture and communicate these stories to the outside world, such as web essays and short videos by our faculty, staff, and students?

c) If Trinity values the open expansion of knowledge, should we offer incentives for faculty in standardized courses (such as introductory statistics, chemistry, psychology, US history) to review, adopt, or create open-access textbooks? Would this investment yield cost-savings for students both at Trinity and elsewhere?

Before taking another ride on the high-technology bandwagon, let’s look at what we truly value as a liberal arts college and identify cost-effective ways to meet our shared goals.

-

Larry Cuban, Teachers and Machines: The Classroom Use of Technology since 1920 (New York: Teachers College Press, 1986), http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/12262353, and his more recent writings at https://larrycuban.wordpress.com/; Audrey Watters, Hack Education, http://hackeducation.com/. ↩

-

Laura Pappano, “The Year of the MOOC,” The New York Times, November 2, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html ↩

-

Steven Leckart, “The Stanford Education Experiment Could Change Higher Learning Forever,” WIRED, March 20, 2012, https://www.wired.com/2012/03/ff_aiclass ↩

-

Carl Straumsheim, “Four Liberal Arts Colleges, Early to the MOOC Scene, Form Online Education Consortium,” Inside Higher Ed, May 13, 2015, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/05/13/four-liberal-arts-colleges-early-mooc-scene-form-online-education-consortium; Ry Rivard, “Despite Courtship Amherst Decides to Shy Away from Star MOOC Provider,” Inside Higher Ed, April 19, 2013, http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/04/19/despite-courtship-amherst-decides-shy-away-star-mooc-provider. ↩