Thank You Lisa Smulyan

A thank-you letter to Lisa Smulyan, who taught me as an undergraduate in the Education Program at Swarthmore College, in celebration of her retirement.

Dear Lisa,

Congratulations on your next life chapter after retiring from Swarthmore! Delighted to see folks organizing an event to celebrate with you. Sorry that I will be away that date so unable to attend in person. But I’ll be thinking of you and the many important life lessons you began teaching me nearly forty years ago in the classroom and in our ongoing conversations.

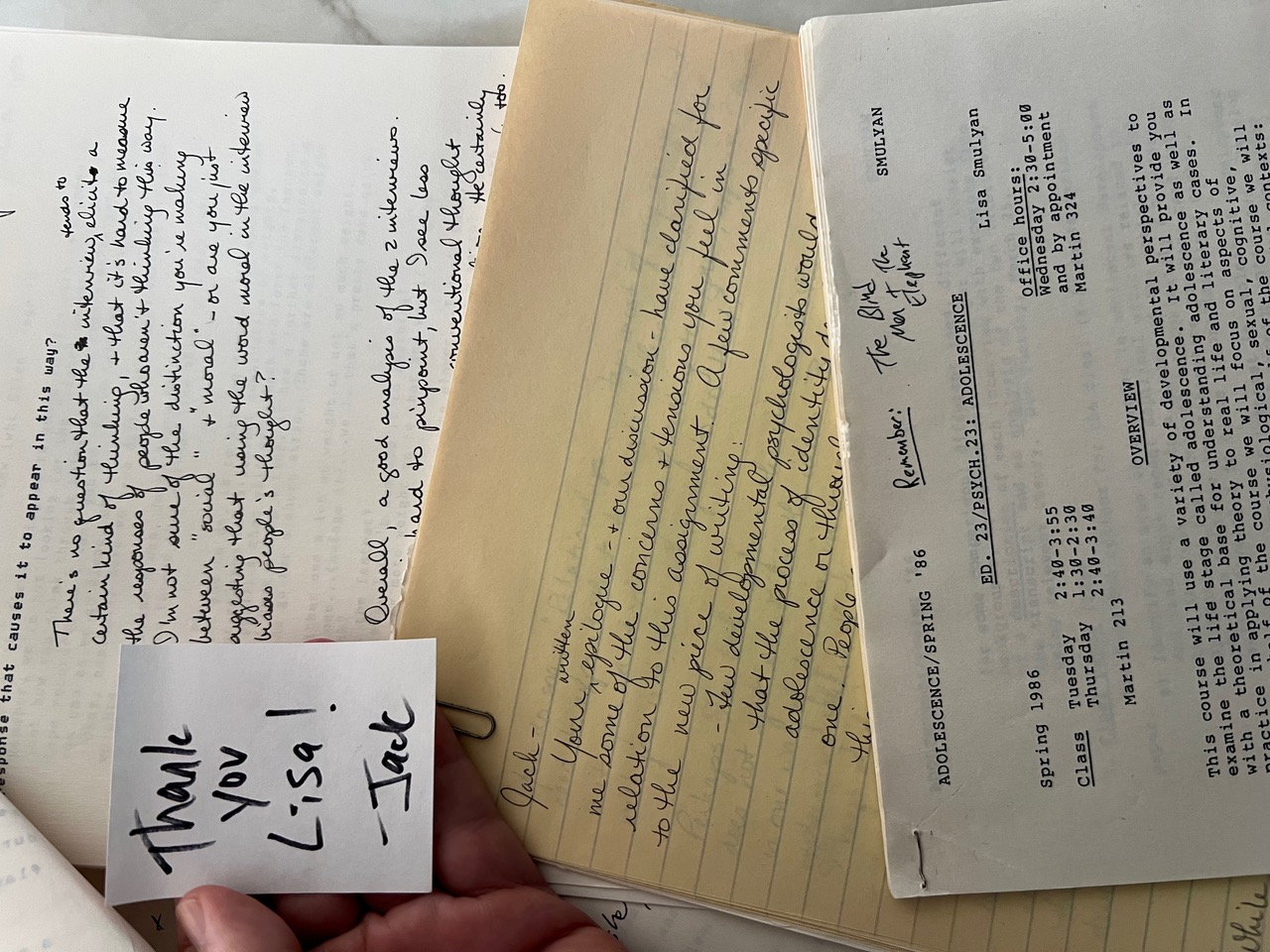

Thank you for putting up with me as a pain-in-the-ass student! In my files I found a dreadful not-so-introspective autobiographical essay I submitted for your Adolescence class in Spring 1986. It’s amazing how much you time you spent with students like me to try to improve our writing. Stapled between my two drafts are two sets of your handwritten notes on yellow paper, each two pages long, and they also reference a discussion you scheduled with each of us (which I still remember!). Looking back it’s clear that my ramblings did not address the goals of the assignment (because in my mind I was challenging its premise), and you correctly pushed me to refocus my “vignettes” and “clearly explain at the beginning of the paper how they all tie together.” At that point in time, I recall not fully grasping what “analysis” meant in this context, and you patiently guiding me on how to dig deeper than “description” and to draw on theories to identify broader patterns, even partial or incomplete. A decade later, when designing our introductory Ed Studies course at Trinity College, I named it “Analyzing Schools” to reinforce what you taught me, defined the term at the top of the syllabus, and continually referred back to it to guide my students while delving into different theories of learning, competing explanations of educational inequality, and divergent strategies to improve schools.

In my second paper for your 1986 class, a cognitive and moral development analysis of two interviews, your comments show that I was starting to get the hang of the type of writing you expected. You and Eva were the only faculty to teach me how to conduct, transcribe, and analyze interviews, a valuable learning process that made abstract concepts much more tangible by closely examining how people spoke and thought on the printed page. (Your example shaped how I subsequently taught high school students, conducted grad school research, and taught research seminars with my own undergrad students.) And once again, at the end of the paper, my pain-in-the-ass self continued to question the assignment. “I would be interested in giving a Gilligan-type moral interview with out mentioning the word ‘moral’ to the adolescent,” I wrote, because asking them to think up a “moral dilemma” seemed to trigger the “abstract context and vocabulary of principled Kohlberg thinking” rather than social tensions in their everyday lives. In your handwritten comments, you clearly engaged with my ideas, treated me like a person who might occasionally be capable of having some worthwhile ones, and continued to nudge me to explain and clarify my wording.

Why did I save these papers? To be clear, I threw away lots of assignments returned by professors who mechanically inserted a letter grade and sparse comments. But I kept papers from you and a few other faculty who made time to engage with my not-yet-well-formed ideas, and to help me communicate the scrambled thoughts in my head more clearly. You cared about me as a student and as a person, and it showed in both your written words and action. Thank you for guiding my growth when I needed it most!

Jack Dougherty ‘87