Reflections on Teaching Educ 350: Writing the Essay Assigned to My Students

When assigning the final essay in our Educ 350: Teaching and Learning course at Trinity College, I decided to place myself in the students’ role and also write my own response. Our assignment was titled “Teaching Reflections: Show Us Your Learning about Building Thinking Classrooms,” which asked us to highlight key themes and show persuasive evidence on our growth as educators this semester, with an emphasis on building thinking classrooms through our developing skills in curriculum design and teaching. In my case, I’m focusing on what I learned while teaching our Educ 350 class this semester. See also my related essay from May 2019

In Spring 2023 I had the opportunity to offer one of my favorite courses with Trinity undergraduates, Educ 350: Teaching and Learning. While many of my more conventional courses require students to analyze schools and systems through syllabus readings and participant-observation, in Educ 350 students advance their higher-order thinking by designing, teaching, and creating web portfolios of three inquiry-based math or science workshops requested by Grade 3-7 teachers at two partnering Hartford public schools: Expeditional Learning Academy at Moylan School (ELAMS) and Environmental Science Magnet at Mary Hooker School (ESM).

The last time I taught Educ 350 was in Spring 2019, and the Covid pandemic and prolonged recovery made it more challenging than usual to set up the course. Many thanks to our Hartford school coordinators Jennifer Doherty (ELAMS) and Kellie Wagner (ESM) for kindly agreeing to recruit classroom teachers, especially during this period of increased stress and high turnover. I’m very grateful to all who made time and space available to help my students learn how to develop their skills as novice educators, especially since Trinity has no official teacher preparation program (this is a standalone elective course) and our Ed Studies budget has very limited resources to offer (about $200 per coordinator and a $20 gift card for each teacher). I’m intentionally including the dollar amount here to reveal – with embarrassment – how little of Trinity’s $140 million budget is allocated to support this course. But the educational benefits to Trinity students are tremendous, in my view. This essay will highlight three themes that stand out when reflecting on what I’ve learned as an educator this semester: 1) Building Pedagogical Thinking through Public Web Portfolios; 2) From Traditional to Inquiry-Based Teaching and Learning; 3) Strong Peer-to-Peer Reviewing Shifted My Teaching Role.

Building Pedagogical Thinking through Public Web Portfolios

Readers who already know me will recognize that I’m a strong believer in students sharing their writing on the public web, with protections for individual student privacy, a theme previously discussed in my chapter in Web Writing (U of Michigan Press, 2015). In this course, students created web portfolios to document their intellectual work as teachers, including lesson plans, images and videos of classroom learning, and their reflections on what worked and what they might do differently next time.

This semester I discovered a deeper analogy in one of our new syllabus readings, Peter Liljedahl’s Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics (Corwin 2021). Liljedahl advances fourteen teaching practices that enhance learning, based on his extensive classroom research. One example is using vertical non-permanent writing surfaces (aka whiteboards) to make students’ mathematical thinking more visible for classroom discussion and contrasting different ways to approach problems. Now I realize that assigning my Trinity students to create public web portfolios of their teaching, and enriching drafts through peer review, makes their pedagogical thinking more visible, not just in our classroom, but to anyone on the web.

In addition, this semester I have emphasized to my students that their teaching portfolios are highly valuable evidence of their teaching work, especially for future employers or graduate programs. Teaching skills are not easily captured in a traditional essay or recommendation letter, but their web portfolios do far better because they are enriched with their lesson plans, images and excerpts from sample student assessments, short video clips of classroom learning in action, and the wisdom accumulated through reflection. Realizing the value of their web portfolios, I incorporated a new final assignment this semester, where students write their own “Teaching Reflection” introduction to their web portfolio and present it to a pair of guest expert evaluators.

Highlights from each of my nine Trinity students’ portfolios:

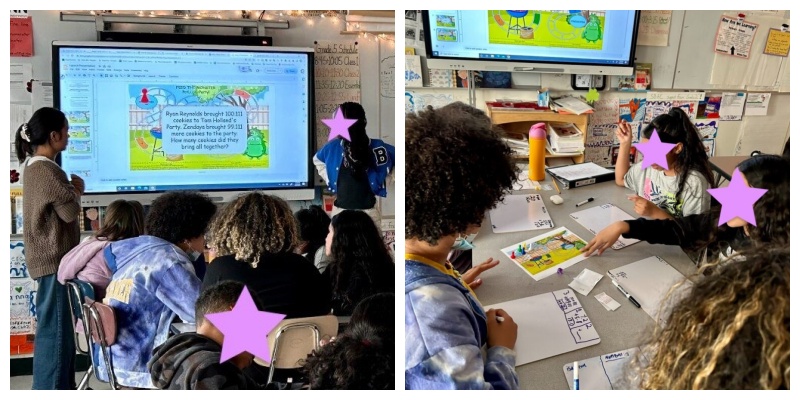

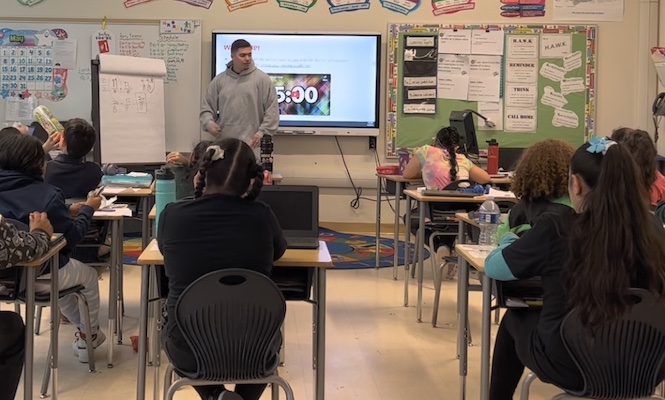

Jessica Cruz designed and led a series of mathematics workshops on adding and subtracting decimals with 5th grade students. In Jess’s final workshop, her class played two different math games, each using word problems written by students, to compare differences between the games and to evaluate which most helped to improve their learning.

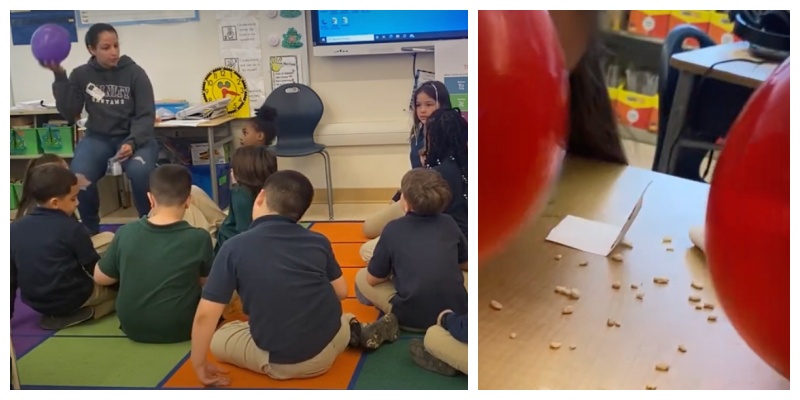

Alberlis Hernandez created and taught three hands-on inquiry-based 5th grade science lessons about forces and motion. In her final lesson, students experimented with the force of static electricity by rubbing balloons to create a charge and testing whether it was strong enough to move different types of materials: paper dots, crispy rice cereal, and styrofoam peanuts.

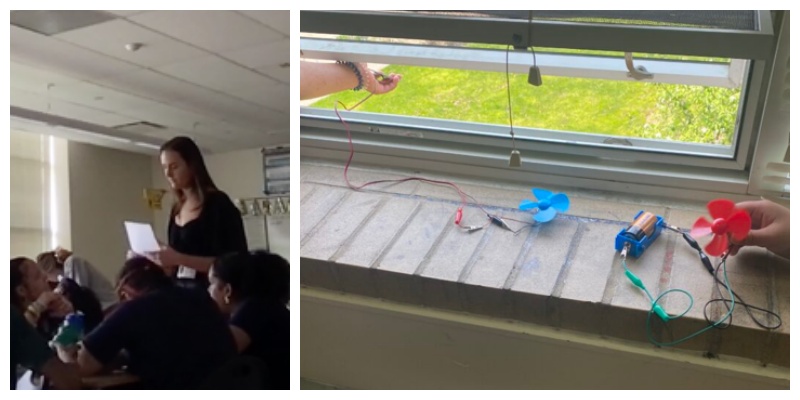

Sloane Latimer designed and led 7th grade science workshops on multiple topics. In Sloane’s final lesson on renewable energy, she led her students in comparing renewable energy collected from mini solar panels to power a small motor versus non-renewable energy stored inside a battery.

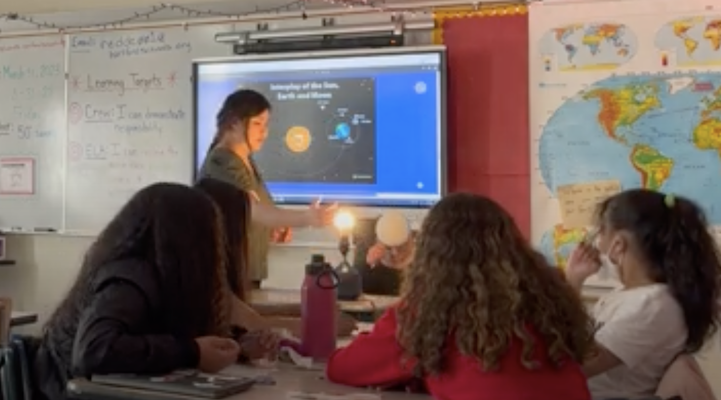

Sonia Lau created and taught three hands-on science lessons with different 5th grade classrooms. In Sonia’s second lesson on phases of the Moon, students moved spheres in their orbits around a bright light, representing the Sun, to simulate how we on Earth perceive light to create different phases: new moon to half moon to full moon.

Maria Markosyan designed and led hands-on workshops that emphasized scientific thinking with 4th grade students. In their first lesson on creating energy with renewable resources, students compared the pros and cons of powering small bulbs and motors with hand-crank generators, batteries, and mini solar cells.

Xavier Mercado innovated with different strategies to help 4th grade students add and multiple fractions greater than one. In Xavier’s final lesson based on the Fortnite video game, students needed to maximize their purchase of quantities of game materials (such as wood and shields) using a price list written in fractions.

Marie Naka created three different hands-on science lessons to promote deeper scientific thinking with 4th grade students. In Marie’s final lesson on the Eggciting Eggsperiment, students tested different strategies to reduce the effect of gravity on a falling egg, using materials such as cotton balls and popsicle sticks.

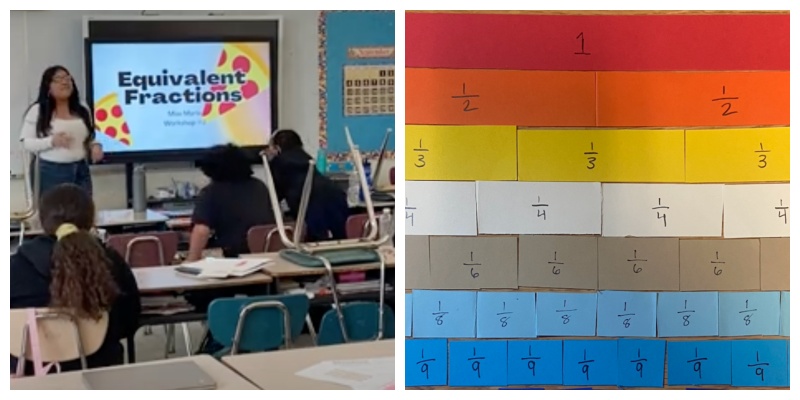

Maria Vicuña innovated with strategies for teaching mathematical thinking with 4th grade students. In Maria’s second lesson on equivalent fractions, she created color-coded fraction bars to help students visualize equal proportions of fractions with different numerators and denominators.

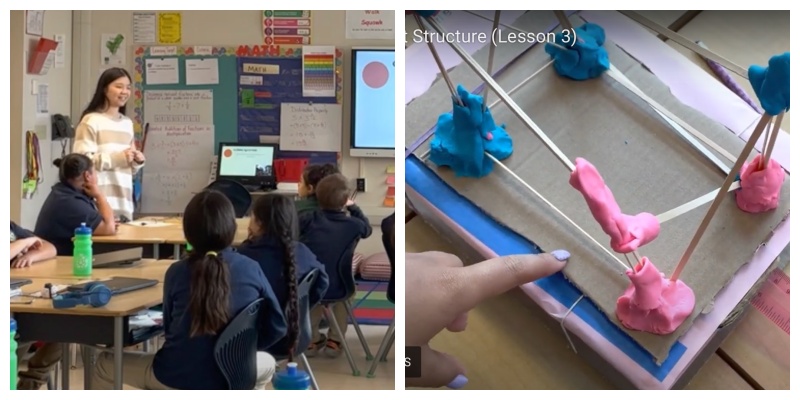

Shelley Xia created and taught three different workshops to promote deeper scientific thinking with 4th grade students. In Shelley’s final lesson on earthquakes, she led students through an activity to design, build, and test earthquake-resistant structures using model buildings they constructed and experimented with on a “shake table.”

From Traditional to Inquiry-Based Teaching and Learning

Newer educators often mimic behaviors – positive or negative – that their own teachers have ingrained into their minds through continuous repetition during twelve or more years of schooling. Since many “traditional” teaching methods do not necessarily spark thinking classrooms (Liljedahl 2021), I consciously try to model different inquiry-based approaches and identify exemplary math and science teaching resources during the first few weeks in our Educ 350 syllabus, when students are preparing their first lessons. For example, at the start of each of the first three classes, we did inquiry-based lessons with guiding questions, such as: 1) Can you light up a light bulb? (about electrical circuits); 2) How much did the temperature drop? (about negative and positive numbers); 3) Growing Shapes (adapted from Jo Boaler, Mathematical Mindsets).

But making the transition from traditional instruction to “inquiry-based learning” or “building thinking classrooms” was not easy for several Trinity students. It’s still surprising to me how strongly many still identify with launching lessons by giving mini lectures, or designing individual worksheets, even when they criticize these traditional approaches during class discussions. I’m still pondering ways to challenge these dominant views. My belief is that novice teachers are more likely to adopt inquiry-based methods if they see and experience rich examples, both in our college classroom and in real K-12 school classrooms. One idea I tried this semester was to arrange for our entire class to visit another school where the new principal (a former math coach) regularly shares rich examples of inquiry-based mathematical thinking by her students and teachers. But my effort failed because we could not arrange a date and time that worked with the school’s already stressed-out teaching staff. The principal encouraged me to try to schedule a visit again next fall, and perhaps I’ll invite former Educ 350 students and others who have not yet enrolled in the course. One can never begin too early.

Strong Peer-to-Peer Reviewing Shifted My Teaching Role

During the semester, I observed a growing number of examples of stronger peer-to-peer guidance and reinforcement of richer teaching methods and reflection. I openly praised individual students, small groups, and the entire class when these examples arose, since it’s my best evidence that Trinity students are authentically growing into their roles as newer educators. Most importantly, watching this transition happen allows me more comfortably shift from my role from “professor” to “coach,” which promotes life-long learning agency for everyone. While I attribute the strength of peer-to-peer learning entirely to my students, one contributing factor may have been small changes I made in our Evaluation Criteria for Lesson Plans and Portfolios, which we used continually, with shorter versions for earlier assignments, to reinforce key principles and “habits of mind” in our course.

See Teaching Reflections and Web Portfolios by Trinity students:

- Jess C https://jessicacruz.domains.trincoll.edu/teaching/

- Alberlis H https://alberlishernandez.domains.trincoll.edu/teaching/

- Sloane L https://slatimer.domains.trincoll.edu/teaching/

- Sonia L https://yantungsonialau.domains.trincoll.edu/teaching/

- Maria M https://mariamarkosyan.domains.trincoll.edu/teaching/

- Xavier M https://xaviermercado.domains.trincoll.edu/teaching

- Marie N https://marienaka.domains.trincoll.edu/teaching/

- Maria V https://mariavicuna.domains.trincoll.edu/teaching/

- Shelley X https://shelleyxia.domains.trincoll.edu/teaching/

Thank you to Trinity Professors Kyle Evans (Mathematics) and Britney Jones (Educational Studies) for serving as guest evaluators for our end-of-semester presentations.